I like astrophotography because it is challenging. A good picture is only partly determined by the quality of optics and mount, the transparency and turbulence of the atmosphere and the darkness of the night sky. A large role is played by how the equipment is actually used: how collimated the optics, how good the polar alignment, how balanced the mount, how accurate the autoguiding, etc. In addition, even after good shots have been taken, the final product can be completely ruined by the unskilled application of image processing techniques. In other words, a really good astronomical photograph is hard to get and comes as the result of optical, mechanical, electrical, and human factors successfully interacting with one another. There is enough learning for a lifetime.

On a good night, however, when everything works as expected and the imaging system pops out pictures as easily as some politicians produce ill-advised tweets, you feel on top of the World (or, at least, Mount Palomar). Yesterday, it felt like one of those rare nights. Everything seemed to work flawlessly as 5 min. subs of the Cave Nebula (Sh2-155) came in from a new ASI294MC camera connected to my faithful GSO 200mm f/4 (CT) Newtonian reflector. In fact, the system behaved so darn well that I went to sleep and left it unattended to complete the four hours of total exposure that I had planned for the night.

In the morning, I woke up refreshed, energized and eager to reap the fruits of my labours. And what fruits did I reap! At the end of the pre-processing stage, this is the picture that showed up in front of my incredulous eyes.

Let’s just say that this was NOT what I hoped for. As I looked in disbelief at this caricature of a photograph, a stream of thoughts rushed through my mind: I cursed the moment I gave up collecting stamps, tried and failed to remember what it felt to have a social life, and pondered whether I could convince anyone that the image was a depiction of the cosmic interplay between Yin and Yang. Those seeds of sanity, however, did not fall on fertile soil. The moment of weakness came and went, and I quickly set out to understand what had happened.

A more careful analysis indicated that things were not as bad they appeared. Far from it. Stars were round and there was no trace of hot pixels: a careful balancing and alignment – combined with generous dithering – had solved two issues with which I had been contending for a while. That was good news. On the other hand, I could not deny that round stars in this context were like well polished handrails on the Titanic. I looked and looked and, no matter how much I wrecked my brain, I simply could not find a cause for so strange a phenomenon.

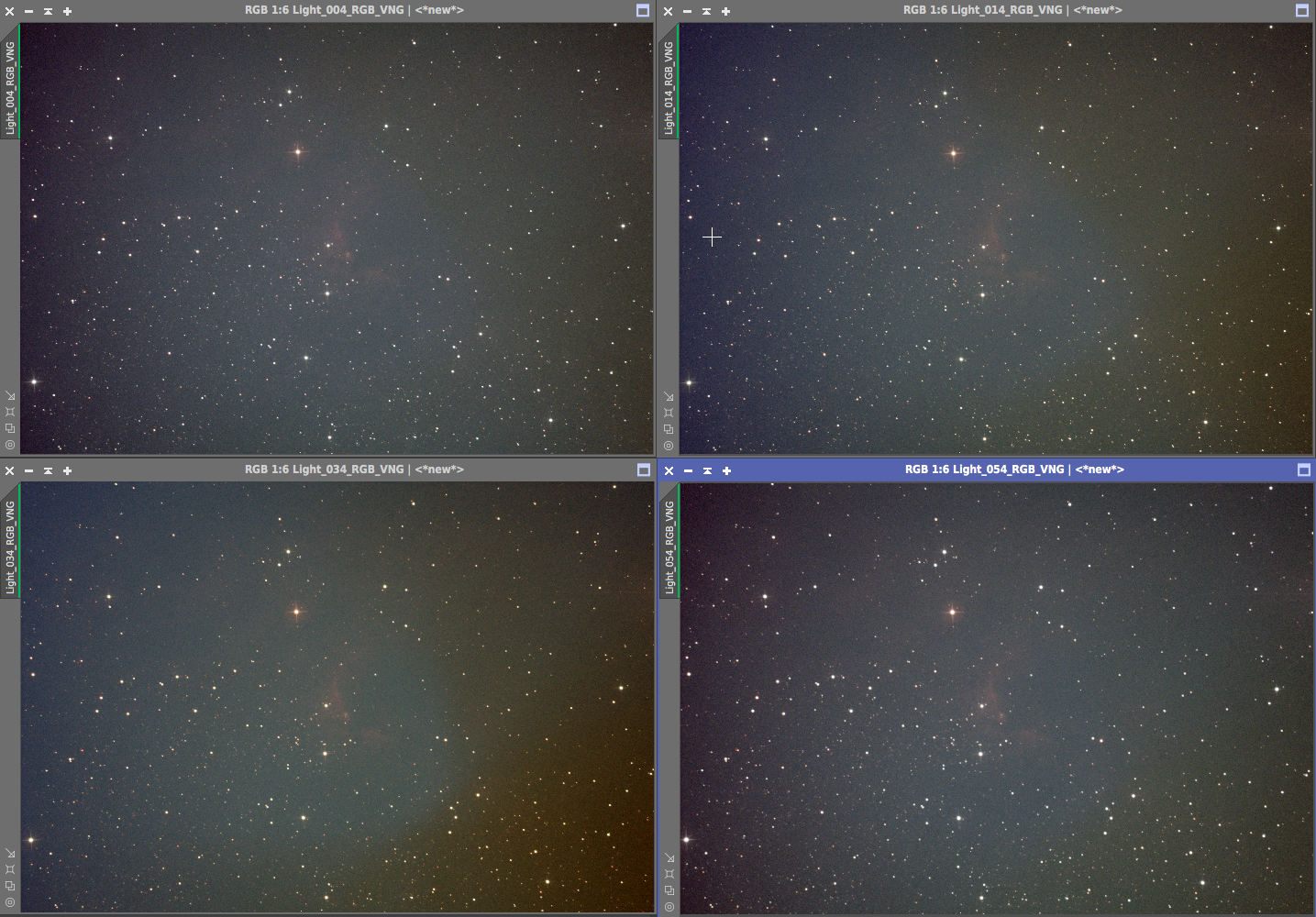

I finally remembered that this monstruosity resulted from the integration of 51 shots taken over the course of four hours. What looked like a blob in the final image could very well come from the combination of simple shadows in the individual pictures. To prove this idea, I compared side by side the first, tenth, thirtieth, and last of the subs.

The shadow seemed to take a different intensity as the telecope swept across the sky to track the nebula. The intensity changed as the telescope moved. It changed… as the telecope moved! Suddenly, from the deepest recesses of my unconscious mind a bone chilling cry emerged. I do not have the heart of repeating the exact words uttered by that ghastly voice. Its reasoning, however, was quite straightforward. The voice started by qualifying in no uncertain terms my skills and mental acuity (examples from the vegetal and mineral world were produced as fitting comparables). It then moved on to cast doubts on the cleanliness, moral integrity and professional inclinations of my ancestors. Finally, it concluded with a remark about how wise it is to leave a brightly lit display close to an instrument whose dearest hope in life is to collect as much light as it possibly can.

And so it was. I had left a laptop pointing towards the back of the telescope. The light from its display leaked through the primary mirror’s cell and was recorded by the camera. The intensity changed as the hours passed because – on its fated course across the sky – the telescope kept moving with respect to the laptop. It was a catastrophe waiting to happen.

I like astrophotography because it is challenging. It does not matter of much attention one puts on any one of its various individual aspects. If one overlooks even the smallest of details, quality suffers. There is enough learning – and laughing for one’s mistakes – for a lifetime.

Brilliantly written!